Melamine: a brief journey from animal feed to cow’s milk

M.Sedak, B. Čalopek, I. Varenina, I. Varga, B. Solomun Kolanović, M. Đokić, A. Končurat and N. Bilandžić*

Marija SEDAK1, sedak@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0001-6861-0436; Bruno ČALOPEK1, calopek@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-0874-

9668; Ivana VARENINA1, kurtes@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-4860-8923; Ines VARGA1, varga@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-

1089-9086; Božica SOLOMUN KOLANOVIĆ1, solomun@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-2498; Maja ĐOKIĆ1, dokic@veinst.hr,

orcid.org/0000-0002-3071-6208; Ana KONČURAT2, koncurat.vzk@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-7520-5751; Nina BILANDŽIĆ1*

(corresponding author), bilandzic@venist.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-0009-5367

1 Laboratory for Residue Control, Department of Veterinary Public Health, Croatian Veterinary Institute, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

2 Veterinary Department Križevci, Croatian Veterinary Institute, 48260 Križevci, Croatia

![]() https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.3

https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.3

Abstract

Melamine is a triazine compound containing 66.6% nitrogen. It is utilised in various industrial applications, including the production of plastics, adhesives, and fertilisers. However, melamine can also contaminate food and animal feed, as it is sometimes added to artificially enhance protein content, which can be toxic to both animals and humans. Notable food contamination incidents involving melamine include the 2007 pet food scandal and the 2008 melamine-contaminated milk scandal in China, which resulted in serious kidney damage and fatalities, particularly among children. The primary health risks associated with melamine arise from its ability to form crystals in the kidneys, potentially leading to renal failure. The body rapidly absorbs and excretes melamine, primarily through urine, as metabolism is minimal. Although acute doses are relatively low in toxicity, long-term exposure, especially through contaminated food, can pose significant health threats. In response to the melamine-related health crises in China, the WHO and EFSA established safe intake levels of 0.2 mg/kg/day for melamine and 1.5 mg/kg/day for cyanuric acid. Various countries have set maximum residue limits for melamine in food, with the United States and China permitting 1.0 mg/kg for infant formula and 2.5 mg/kg for other dairy products. In Europe, the limits are stricter, at 1.0 mg/kg for powdered infant formula, 0.1 mg/kg for liquid formula, and 2.5 mg/kg for foods. The determination of melamine and cyanuric acid in food and feed presents significant challenges. Advanced techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry are the most commonly employed methods.

Key words: melamine; cyanuric acid; contamination; milk; powder milk; feed; detection

Introduction

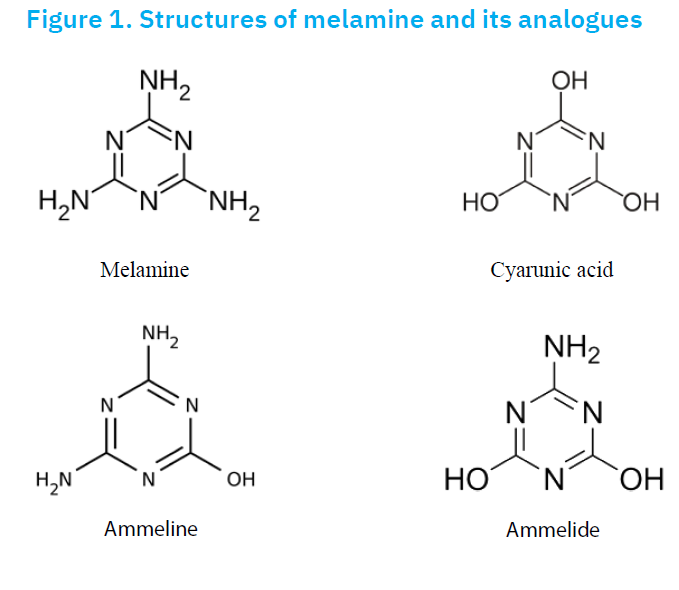

Melamine is a triazine compound with the molecular formula of C3H6N6 with a 66.6% nitrogen content. German chemist Justus von Liebig first synthesised melamine in 1834 by heating potassium thiocyanate with ammonium chloride (Zhang et al., 2007). Pure melamine is a very thermostable crystalline substance and can be hydrolysed through deamination reactions, under strongly acidic or alkaline conditions, to form cyanuric acid (2,4,6-trihydroxy-1,3,5-triazine), ammeline (4,6-diamino-2-hydroxy-1,3,5-triazine), and ammelide (6-amino-2,4-dihydroxy-1,3,5-triazine) (Fig. 1). The first use of melamine dates back to 1930 when it was combined with formaldehyde to produce a variety of products, including melamine foam and thermosetting plastics. Melamine is a widely utilised component in the manufacturing of various industrial products worldwide (Fig. 2), though it is believed that melamine may leach from these products (Ingelfinger, 2008). In addition, it has a diverse range of industrial and domestic applications, including adhesives, laminates, paints, permanent-press fabrics, flame retardants, textile finishes, tarnish inhibitors, paper coatings, and fertiliser mixtures (Liu et al., 2012). Due to its high nitrogen content, melamine was initially employed as a cost-effective protein alternative in cattle and pet feed. It is a metabolite and degradation product of the pesticide and veterinary drug cyromazine (Mariana et al., 2013). Residues of cyanuric acid can also be found in food following the use of dichloroisocyanurates as a source of active chlorine in disinfection agents. Both melamine and cyanuric acid can be present as impurities in urea-based feed for ruminants (EFSA, 2010).

Food contamination remains a significant issue in contemporary society. To mitigate this risk, food production is meticulously monitored throughout the entire supply chain. The laws and policies established for this purpose create a framework that supports both the global and European food trade while safeguarding public health and, whenever possible, protecting animals, plants, and the environment. In 2010, melamine was identified as an emerging contaminant in numerous countries due to incidents stemming from its illegal use. Notable cases include the contamination of pet food in North America in 2007 and the tainting of fresh milk, certain powdered milk formulas, eggs, and other products in China in 2008 (WHO, 2009). Melamine was illicitly added to food products to artificially enhance protein content, leading to severe health consequences for both humans and animals in these instances. The pet food contamination in North America in 2007 resulted in an outbreak of renal disease and the deaths of hundreds of cats and dogs in the United States. Additionally, the melamine milk scandal in China in 2008 prompted analysts to urgently develop effective testing methods for detecting melamine in animal feed and milk samples.

Melamine toxicity

Adulteration of food and feed materials is a major concern, not only because it increases the danger of economic losses for purchasers, but also because it poses significant health hazards to consumers. Protein concentrates are the leading cause of food chain contamination with melamine and cyanuric acid (Suchy et al., 2009).

Large-scale epidemics of renal failure and deaths of cats and dogs in the USA, Canada, and South Africa in 2007 were linked to nephropathy caused by kidney crystals containing cyanuric acid and melamine (FDA, 2008). According to the Veterinary Information Network, between 2000 and 7000 dogs and cats are thought to have died as a result of eating pet food tainted with cyanuric acid and melamine (Puschner and Reimschuessel, 2011).

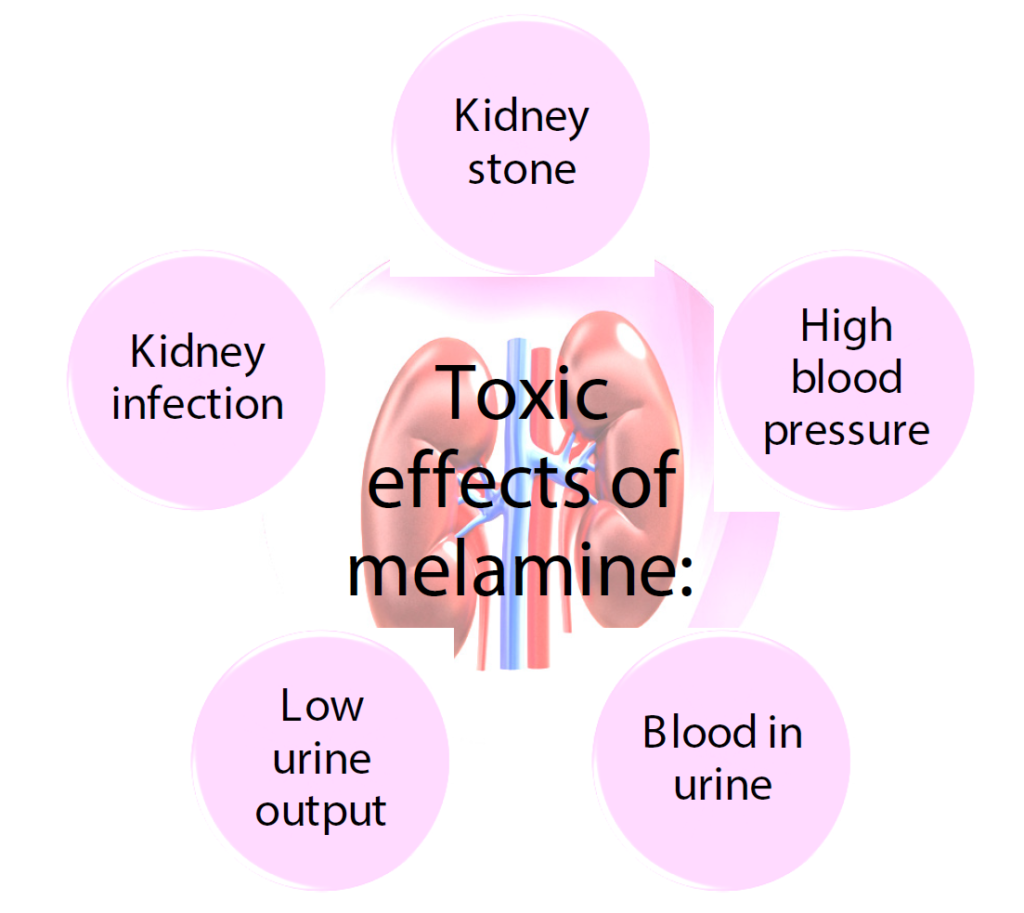

The melamine-contaminated milk incident in China was one of the most serious events, particularly since young children are relatively vulnerable to food contaminants. At least six children died in China from severe kidney failure due to the melamine added to milk powder, and more than 200,000 infants and young children were affected by kidney problems with more than 50,000 hospitalisations (EFSA, 2010). The seriousness of melamine adulteration and the subsequent kidney damage (Fig. 3) brought attention to the urgent need to protect the public health (Brown et al., 2007).

Figure 3. Toxic effects of melamine

The toxicokinetics of melamine involve rapid absorption and excretion via the kidney with essentially no metabolism or elimination. The half-life in monogastric mammals is approximately 4–5 hours. The scarce toxicokinetic information available for cyanuric acid also shows that it is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal system, rapidly excreted through the urine, and undergoes little to no biotransformation. Its plasma half-lives vary from a few hours in mammals to nine hours in rainbow trout (Xue et al., 2011). Toxicity of melamine results from the formation of crystals in the urinary tract, consisting of complexes of melamine with uric acid occurring naturally in urine, or with cyanuric acid if co-exposure occurs. The formation of these complexes is strongly influenced by melamine content and by urine composition, particularly parameters such as pH and uric acid. In conclusion, melamine and cyanuric acid are primarily excreted through renal pathways in the majority of animal species, exhibiting minimal metabolic transformation and a relatively short half-life of several hours. An exception to this pattern is observed in rainbow trout, where the half-lives of melamine and cyanuric acid are approximately 30 hours and 8 hours, respectively (Dorne et al., 2013).

Outside of China, there have been no documented instances of adverse effects associated with food products containing melamine. Furthermore, numerous countries worldwide have implemented restrictions on imports of products from China that may contain trace amounts of melamine. In instances where melamine was deliberately added to milk, concentrations of up to 2.5 g/kg of product have been detected. Although the lethal dose (LD50) of melamine for humans has not been established, toxicity studies conducted on laboratory animals indicate that melamine exhibits low acute toxicity. The lowest oral 50% LD50 recorded was in male rats, at 3828 mg/kg body weight. Similar LD50 values were observed in female rats and male mice, while a higher LD50 was noted in female mice (Melnick et al., 1984).

On 18 March 2010, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issued a scientific opinion at the request of the European Commission concerning the presence of melamine in feed and food. The findings indicated that exposure to melamine can lead to the formation of crystals within the urinary tract, which in turn can cause proximal tubular damage. Such crystalline formations have been documented in both animals and children following incidents of melamine adulteration in feed and infant formula, with some cases resulting in fatalities. In response to these concerns, the Codex Alimentarius Commission has established maximum permissible levels of melamine in feed and food products. For the purpose of safeguarding human health, it was deemed necessary to incorporate these maximum levels into Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006, which was subsequently amended to Regulation (EC) No 915/2023, as these levels align with the conclusions drawn in the EFSA opinion (EC, 2023).

Occurrence of melamine in feed

Following complaints of pet illnesses and liver failure fatalities in the United States starting in February 2007, melamine was confirmed to be the cause of the major recall of over 100 name-brand pet food products in the preceding year (Burns, 2007).

United States authorities initiated an investigation to identify the source of the animal health issues that had arisen. It was determined that the problems originated from wheat gluten imported from China, which was utilised in the production of pet food. Subsequent investigations indicated that melamine, an industrial chemical characterised by its high nitrogen content and commonly used in the manufacture of plastics, had likely been illicitly added to wheat gluten and other protein sources to artificially inflate their protein content. Additionally, melamine and cyanuric acid were detected in rice protein concentrate imported from China. Furthermore, melamine was also identified in South Africa in corn gluten sourced from China (FDA, 2008).

Currently, there are no approved applications for the direct addition of melamine into animal feed. However, melamine may be detected in animal feed as a result of its presence in feed ingredients derived from crops at baseline concentrations, or through the use of feed additives and cyromazine, which is employed as a veterinary pharmaceutical (Karras et al., 2007). The industrial production of melamine generates millions of tons of waste. Due to its high nitrogen content, this melamine waste is frequently used as a fertiliser for crops in various countries. It has been proposed that melamine is assimilated into the soil and subsequently absorbed by plants (Ingelfinger, 2008).

Cyromazine, a triazine pesticide, is utilised in agricultural practices to inhibit insect development and control flies on fruits, vegetables, and field crops. This pesticide is prone to degradation when exposed to light or elevated temperatures, leading to the formation of melamine. Furthermore, it may undergo environmental degradation or dealkylation reactions as part of standard plant metabolic processes. This phenomenon represents an alternative pathway via which melamine can be present in plant material, independent of direct application to the plants or soil (Sancho et al., 2005; Muñiz-Valencia et al., 2008).

A series of experiments was performed to evaluate the efficacy of melamine as a potential nitrogen source for plants. One notable finding indicated that approximately 1% of the nitrogen from melamine was converted to nitrate, in contrast to the 80% conversion rate observed for nitrogen from ammonium sulfate. These results further corroborate the classification of melamine as a slow-release nitrogen fertiliser (Allan et al., 1989).

Melamine transmission to milk

A 2008 study at Stellenbosch University in South Africa investigated the transfer of melamine from feed to milk, and the findings supported the initial hypothesis. Specifically, it was observed that when cows ingested melamine-contaminated feed, detectable levels of melamine were present in milk as soon as 8 hours post-consumption. Furthermore, even after the cows were removed from the melamine-laden diet, traces of melamine remained in the milk for a duration of up to 7 days (Cruywagen et al., 2009).

On the second day of the feeding period, melamine was found to have passed from feed to milk in the milk of every group that received melamine treatment. In all melamine-treated groups, mean milk melamine concentrations elevated steadily over the first three days of the feeding period before considerably fluctuating over the next ten days. Cruywagen et al. (2009) discovered that melamine could transfer from feed to milk at an efficiency rate of 2% when consumed at a level of 17.1 g/day. Based on this efficiency rate, raw milk from dairy cows producing 20 kg milk and consuming 125 or 320 mg melamine daily should not be used for producing infant formula powder or regular milk powder, respectively. Higher-producing cows seem to be able to excrete more melamine than lower-producing cows. A similar outcome regarding the transfer of aflatoxin from feed to milk in dairy cows was discovered by Masoero et al. (2007), who concluded that the primary factor influencing the total excretion of aflatoxin M1 was milk yield.

The adulteration of animal diets is the primary cause of melamine contamination in milk and milk products, rather than the intentional addition of harmful ingredients. Following a single instance of consumption, it takes a minimum of seven days for melamine to be completely eliminated from milk. The cheese-making process demonstrates that whey absorbs nearly all of the melamine present. Health concerns regarding the consumption of milk and its by-products—such as whey—arise only when cow diets exceed the European permitted limits for feed. In such cases, the maximum assessed contamination level of 50 g/day in cheese could pose a significant risk to human health (Battaglia et al., 2010).

Occurrence of melamine in milk and dairy products

Milk serves as a primary source of vital nutrients, including proteins, fats, carbohydrates, and vitamins, essential for both adults and infants. However, the adulteration of milk presents a significant global challenge. Several factors contribute to this issue, including the substantial gap between supply and demand, the perishable characteristics of milk, the limited purchasing power of consumers, and the lack of effective testing methods for detecting milk adulteration (Kamthania et al., 2014).

Milk and infant formula adulterated with melamine has been of high concern since September 2008, when more than 294,000 children suffered kidney and urinary problems in China following the ingestion of melamine-contaminated formula. As a result, 52,000 infants were hospitalised, with at least six fatalities due to this illegal practice. The highest concentration of melamine detected in milk was as high as 2,563 mg/kg (EFSA, 2010; Wen et al., 2016). Contamination was also identified in milk-based products, such as milk powder in Africa. Additionally, 6% of samples contained melamine at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 5.5 mg/kg (Schoder and McCulloch, 2019).

In China, a significant number of raw milk producers are small-scale household farmers who are motivated to enhance milk production yields due to the pressures of low market prices and increasing grain costs. The government has established nutritional standards for milk, particularly for infant formula, which necessitate higher protein content. In response, farmers have resorted to the addition of melamine to milk as a cost-effective means of meeting these requirements. Furthermore, intermediaries operating between milk producers have been acquiring substandard milk at reduced prices, also incorporating melamine to elevate protein levels, and subsequently selling this adulterated milk to dairy companies at inflated prices (Pei et al., 2011; Li et al., 2019).

Melamine can contaminate milk and dairy products through several pathways, including: adulteration of milk products to create protein, the use of the insecticide cyromazine on crops, the application of nitrogenous fertilisers (with melamine serving as a nitrogen source), consumption of crops contaminated with melamine or cyromazine, and transfer from polymers used in milk packaging materials (Yang et al., 2009; Honkar et al., 2015).

Cows grazing on melamine-fertilised pastures will absorb the chemical into their milk and tissues. Melamine can be transferred from grass to milk after eight hours, with an efficiency of 3% for pastures with low melamine concentrations and 2.1% for those with high melamine concentrations (Cruywagen et al., 2009).

After the incidents of milk adulteration with melamine, which resulted in the formation of melamine-uric acid and led to the hospitalisation and deaths of children in China, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain of the EFSA reassessed the tolerable daily intake (TDI) value for melamine. WHO and EFSA have recommended TDIs of 0.2 mg/kg/day for melamine and 1.5 mg/kg/day for cyanuric acid (WHO, 2008; EFSA, 2010). To safeguard public health and ensure food safety, many countries have established maximum residue limits (MRLs) for melamine in various products (EFSA, 2010; Filazi et al., 2012). In the United States and China, maximum levels for infant formula have been set at 1.0 mg/kg for milk and 2.5 mg/kg for other dairy products (Domingo et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2016). In Europe, EFSA has established limits for infant formula, follow-on formula, and young child food at 1.0 mg/kg for powdered formula and 0.1 mg/kg for formula marketed as liquid. For other foods, the MRL is set at 2.5 mg/kg for all products containing more than 15% milk (EC, 2023).

Detection of melamine in food and feed

The Kjeldahl method, which is used in routine protein measurement experiments, cannot distinguish between protein and non-protein nitrogen. Melamine contamination in milk and milk products is caused by both external addition and adulteration of animal diets. Cows that consume melamine may provide a major health danger to users of milk and dairy products. To avoid human melamine exposure through milk consumption, raw material and animal feed production should be closely monitored (Chu et al., 2010).

Screening methods usually yield results more quickly than selective techniques; however, they lack the ability of mass spectrometry-based methods to unambiguously identify melamine and related compounds. Consequently, if a sample tests positive using a screening method, it is essential to verify the results with confirmatory methods that offer greater selectivity and sensitivity (Kim et al., 2008).

Modern instrument analytical methods that have been developed to detect the presence of melamine in milk are capillary electrophoresis (CE), matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrophotometry (MALDI-MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), micellar liquid chromatography (MLC), liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrophotometry (LC–MS/MS), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Modern instrument analytical methods also include capillary electrophoresis (CE), matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrophotometry (MALDI-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Liu et al., 2012; Chilbule et al., 2019).

The FDA originally established a GC–MS screening technique that involved the derivatisation of melamine in sample extracts using a trimethylsilyl (TMS) reagent prior to analysis (FDA, 2008). This methodology has since been enhanced through the implementation of gas chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (GC–MS/MS) and the use of 2,6-diamino-4-chloropyrimidine as an internal standard (IS). Nonetheless, the instrumentation associated with these methodologies is costly, and the sample pre-treatment process is labour-intensive (Liu et al., 2012; Scano et al., 2014).

In recent years, HPLC has emerged as one of the most effective methodologies for the analysis of biological matrices and pharmaceutical formulations, attributable to its high efficiency and excellent reproducibility (Tittlemier, 2010; Abedini et al., 2021). Nevertheless, HPLC is not a very reliable approach for identifying melamine and is not always able to confirm target analytes. The ultraviolet (UV) spectra of melamine exhibit absorption characteristics below 250 nm, which may lead to inaccurate quantification if adequate attention is not given to the chromatographic conditions and the optimisation of samples. Samples must be extracted, purified, and derivatised as part of the lengthy, expensive, and time-consuming sample preparation required by MALDI-MS techniques (Sun et al., 2010).

Among the most dependable and sensitive techniques for melamine detection and quantification in a variety of food and feed products are HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), which today is used most often for routine analysis of melamine in adulterated milk (Tkachenko et al., 2015; Chilbule et al., 2019; Nagraik et al., 2021).

Conclusions

Melamine, a nitrogen-containing industrial compound, is widely used in numerous industries; however, its misuse as a protein adulterant in food and feed has led to significant public health crises. The low production cost of melamine makes it attractive for fraudulent adulteration of food and feed to artificially increase protein content, resulting in significant health risks to humans and animals when ingested. The kidneys are the most commonly reported site of melamine or melamine cyanuric acid toxicity.

Several analytical methods have been developed for the detection of melamine in various matrices, including food, feed and environmental samples. This overview highlights the importance of a comprehensive understanding of the risks posed by melamine, and the need for continuous improvements of detection methods to mitigate the negative impacts on human health and the environment. Among the most reliable and sensitive methods for the detection and quantification of melamine in a variety of food and feed products is HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), which is most commonly used today for the routine analysis of melamine in adulterated milk. Continuous research and innovation are essential to further improve the detection capabilities of melamine and ensure the safety of food and feed.

References [… show]

Melamin – kratak put od hrane za životinje do kravljeg mlijeka

Marija SEDAK1, sedak@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0001-6861-0436; Bruno ČALOPEK1, calopek@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-0874-9668; Ivana VARENINA1, kurtes@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-4860-8923; Ines VARGA1, varga@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-1089-9086; Božica SOLOMUN KOLANOVIĆ1, solomun@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-2498; Maja ĐOKIĆ1, dokic@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-3071-6208; Ana KONČURAT2, koncurat.vzk@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-7520-5751; Nina BILANDŽIĆ1* (dopisni autor), bilandzic@venist.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-0009-5367

1 Laboratorij za određivanje rezidua, Odjel za veterinarsko javno zdravstvo, Hrvatski veterinarski institut, 10000 Zagreb, Hrvatska

2 Veterinarski zavod Križevci, Hrvatski veterinarski institut, 48260 Križevci, Hrvatska

Melamin je triazinski spoj bogat dušikom koji sadrži 66,6 % dušika. Brojne se njegove primjene u industriji, uključujući plastiku, ljepila i gnojiva. Međutim, melamin može kontaminirati hranu i hranu za životinje, jer se dodaje u svrhu povećanja sadržaja proteina, a što može imati toksične posljedice za ljude i životinje. Najznačajniji skandali povezani s melaminom uključuju kontaminaciju hrane za kućne ljubimce 2007. godine te kontaminaciju mlijeka u Kini 2008. godine, koja je rezultirala ozbiljnim oštećenjem bubrega i smrtnim slučajevima, osobito među djecom. Primarni zdravstveni rizici melamina proizlaze iz njegove sposobnosti stvaranja kristala u bubrezima, što može prouzročiti zatajenje bubrega. Tijelo brzo apsorbira i izlučuje melamin, prvenstveno kroz urin, unutar 24 sata. Iako su akutne doze relativno niske toksičnosti, dugotrajna izloženost, osobito putem kontaminirane hrane, može predstavljati značajnu prijetnju zdravlju. Nakon zdravstvene krize povezane s melaminom u Kini, WHO i EFSA uspostavile su sigurne razine unosa od 0,2 mg/kg/dan za melamin i 1,5 mg/kg/dan za cijanurnu kiselinu. Pojedine zemlje postavile su najveće dopuštene količine za melamin u hrani te u SAD i Kini iznose 1,0 mg/kg za hranu za dojenčad i 2,5 mg/kg za ostale mliječne proizvode. U Europi su ograničenja stroža, odnosno 1,0 mg/kg za hranu za dojenčad u prahu, 0,1 mg/kg za tekuću formulu i 2,5 mg/kg za hranu. Određivanje melamina i cijanurne kiseline u hrani i hrani za životinje je izazovno. Najčešće se primjenjuje napredna tehnika tekućinske kromatografije visoke učinkovitosti (HPLC) i tandemske masene spektrometrije (MS/MS).

Ključne riječi: melamin, cijanurna kiselina, kontaminacija, mlijeko, mlijeko u prahu, hrana za životinje, detekcija