N-Acetylcysteine in Dogs and Cats: Pharmacokinetics, Therapeutic Effects and Antioxidant Function

M. Y. Nur Mahendra, H. Pertiwi, T. Bhawono Dadi, M. Soneta Sofyan* and J. Kamaludeen

Mohamad Yusril NUR MAHENDRA1; Herinda PERTIWI1; T. BHAWONO DADI2; M. SONETA SOFYAN1*; (corresponding author),

miyayu@vokasi.unair.ac.id; Juriah KAMALUDEEN3

1 Department of Health Studies, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Airlangga University, Jalan Dharmawangsa Dalam 28-30,

60286 Surabaya, Indonesia

2 Department of Veterinary Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Airlangga University, Jalan Mulyorejo 60115 Surabaya, Indonesia

3 Department of Animal Science and Fishery, Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, University Putra Malaysia, Bintulu Sarawak Campus,

97008 Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia

![]() https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.6

https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.6

Abstract

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a derivative of the amino acid cysteine, is widely recognised for its diverse pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and mucolytic effects. As a precursor to glutathione, NAC plays a critical role in maintaining redox balance and mitigating oxidative stress, thereby preventing cellular damage caused by reactive oxygen species. While NAC has been extensively studied in human medicine, its application in veterinary medicine, particularly in dogs and cats, has gained growing interest in recent years. Beyond its antioxidant action, NAC exhibits clinically relevant anti-inflammatory and mucolytic effects, positioning it as a valuable therapeutic agent for managing hepatic, respiratory, and toxicological conditions in small animals. This review aims to synthesise the current knowledge on the pharmacokinetics, therapeutic applications, and species-specific considerations of NAC in canine and feline medicine, highlighting its potential to fill important gaps in oxidative stress management and supportive therapy in veterinary practice.

Key words: Antioxidant; Cat; Dog; N–acetylcysteine

Introduction

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has garnered increasing attention as a therapeutic agent, supported by emerging evidence that highlights its clinical utility beyond its well-established functions as an antidote and antioxidant (Yahia et al., 2024). Recent studies have underscored its mucolytic properties, suggesting a potential role in alleviating disturbances in salivary gel consistency when administered therapeutically. Although salivary gland disorders are relatively rare in veterinary medicine, they are most frequently reported in feline and canine patients, with an estimated incidence of approximately 0.3% based on clinical diagnostic reports (Kim et al., 2024).

In Europe, NAC is commercially available in injectable formulations ranging in concentrations from 10% to 20% for specific clinical indications in veterinary settings. In the United States, although NAC is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use, its application in veterinary medicine is permitted under extra-label use provisions (Ortillés et al., 2020; Rague, 2021).

Structurally, NAC is an N-acetylated derivative of the endogenous amino acid L-cysteine, a critical precursor in the biosynthesis of glutathione. This characteristic underpins its therapeutic value, particularly in conditions involving enzyme deficiencies, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) intoxication (Tieu et al., 2023). While acetaminophen is widely regarded as a safe and effective antipyretic and analgesic in human medicine, it presents a significant toxicological risk to veterinary patients and is among the most frequently reported causes of toxicity in canine and feline clinical practice (Bello and Dye, 2023). The hepatotoxicity associated with acetaminophen is primarily due to the formation of a reactive metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), which induces oxidative stress and cellular damage in susceptible species, including dogs, cats, non-human primates, ferrets, birds, and pigs (Ben-Shachar et al., 2012). Most cases of acetaminophen poisoning in companion animals result from inadvertent or inappropriate administration by pet owners without veterinary consultation.

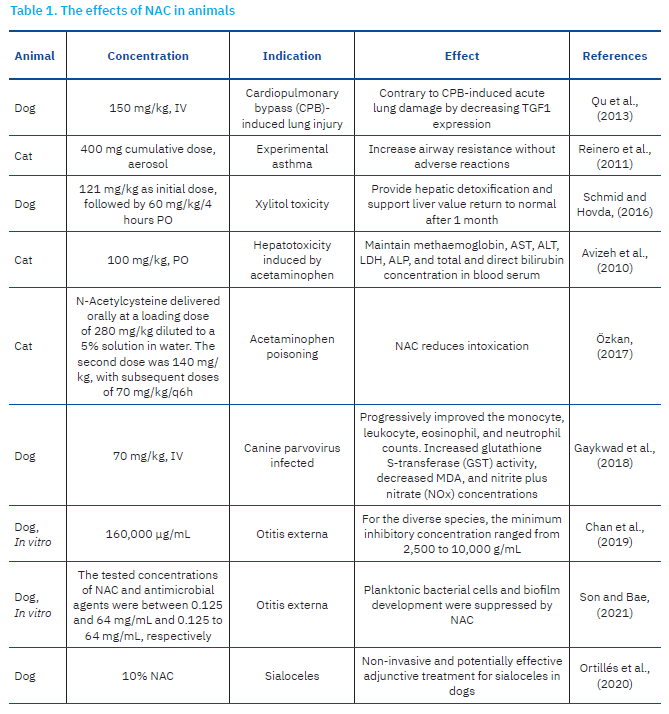

Beyond its role in glutathione biosynthesis, NAC has also been recognised for its regulatory effects on antibiotic activity within bacterial systems. Its ability to inhibit pathogenic biofilm formation and enhance the antimicrobial efficacy of conventional antibiotics has been widely documented (May et al., 2019; Chlumsky et al., 2021). Despite these promising findings, there remains a notable lack of comprehensive reviews focused specifically on the use of NAC in canine and feline populations. To address this gap, the present review examines the multifaceted effects of NAC in dogs and cats, with emphasis on its pharmacological properties and its antioxidant, mucolytic, antibacterial, and detoxifying activities (Table 1).

Pharmacology and Oral Bioavailability

N-acetylcysteine has long held a respected place in both human and veterinary medicine as an inexpensive, multifunctional therapeutic agent (Izquierdo Alonso et al., 2022). While cysteine is naturally abundant in dietary sources such as poultry, yogurt, garlic, and eggs, NAC itself is a synthetic compound not directly obtained from food intake (Larsson et al., 2015). Interestingly, organosulfur compounds bearing NAC-like structures have been identified in Allium species, with Allium cepa (red onion) containing approximately 45 mg/kg (Dorrigiva et al., 2021). Chemically, NAC’s molecular formula (HSCH₂CH(NHCOCH₃)CO₂H) and molecular weight (163.19 g/mol) reflect its defining features, particularly the thiol group responsible for its antioxidant and reducing actions, and the acetyl group, which modulates solubility, stability, and membrane interactions (Rind et al., 2021).

Despite its pharmacological potential, NAC is marked by poor and highly variable oral bioavailability across species, primarily due to rapid gastrointestinal deacetylation and extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism (Teder et al., 2021). Intestinal and hepatic deacetylases rapidly convert NAC into free cysteine before it reaches systemic circulation, limiting the fraction of intact drug available for therapeutic action. In humans, oral bioavailability ranges from 4–10% (Buur et al., 2013; Teder et al., 2021), while in cats, it is slightly higher (19.3 ± 4.4%) (Sun et al., 2023). However, robust pharmacokinetic data in dogs are scarce, with current veterinary dosing protocols often extrapolated from non-canine models or based on limited empirical evidence. This lack of species-specific pharmacokinetic data represents a major barrier to the rational development of optimised, evidence-based therapeutic regimens in veterinary practice.

Once absorbed, NAC engages several key metabolic pathways. Its primary route involves deacetylation to cysteine, which subsequently feeds into glutathione (GSH) synthesis, the body’s principal intracellular antioxidant and redox regulator. Additional metabolic processing includes sulfation and glucuronidation within the liver, followed by renal excretion (Pedre et al., 2021). Importantly, the efficiency of these metabolic pathways is influenced by species-specific differences, age, health status, and hepatic enzymatic capacities, all of which contribute to the wide interindividual and interspecies variability observed in pharmacokinetics and therapeutic outcomes. Although NAC crosses the blood–brain barrier (BBB) inefficiently, its capacity to elevate systemic cysteine levels can indirectly increase cerebral GSH concentrations, offering potential neuroprotective benefits (Coles et al., 2018), a feature of growing relevance to veterinary applications targeting oxidative stress-related central nervous system conditions.

Pharmacokinetic studies indicate that NAC exhibits rapid systemic degradation, with a notably short elimination half-life: approximately 0.78 h after intravenous administration and 1.34 h following oral dosing in cats (Sun et al., 2023). Renal clearance, primarily through glomerular filtration, constitutes the major excretory route, with minimal recovery of unchanged parent compound in urine (Barreto et al., 2021).

The inherent physicochemical properties of NAC further constrain its oral absorption. Its hydrophilic, ionised nature impedes passive transcellular diffusion across the lipid-rich intestinal epithelium, while its instability under acidic gastric conditions reduces luminal availability before reaching the small intestine (Rind et al., 2021). Compounding these limitations, species-specific variations in intestinal transporter systems, portal haemodynamics, gastrointestinal enzymatic activity, and hepatic metabolic processing amplify absorption and disposition differences between dogs, cats, and humans. For instance, dogs possess unique profiles of amino acid transporters and hepatic enzyme activities compared to cats, potentially impacting NAC’s pharmacokinetics and therapeutic responsiveness. Yet, detailed veterinary-focused studies dissecting these mechanistic differences are surprisingly lacking, underscoring the urgent need for targeted research to guide precise, species-adapted interventions.

To address the widely recognised challenges associated with NAC’s limited bioavailability, several innovative delivery and formulation strategies have been explored, although their veterinary applications remain underdeveloped. Liposomal encapsulation of NAC within α- or γ-tocopherol-enriched carriers has been shown to enhance gastrointestinal stability, protect against enzymatic degradation, and extend systemic retention. For example, Alipour et al. (2013) demonstrated that dogs receiving liposomal NAC exhibited significantly elevated plasma concentrations compared to those administered conventional oral formulations, suggesting an effective approach for improving oral delivery in veterinary settings. Alternatively, lipophilic NAC derivatives such as N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) offer enhanced membrane permeability, superior in vivo stability, and improved BBB penetration compared to native NAC (Atlas et al., 2021). While not yet routinely used in veterinary medicine, NACA’s pharmacokinetic advantages hold substantial promise, particularly for addressing neurological or central nervous system conditions in canine and feline patients. Co-administration with absorption enhancers, such as vitamin E, bile salts, or surfactants, has also shown potential to improve intestinal permeability and reduce premature enzymatic degradation. Notably, studies in hospitalised dogs have demonstrated that combined NAC and vitamin E therapy not only improves antioxidant capacity, but also enhances clinical outcomes (Hagen et al., 2021), indicating the value of synergistic therapeutic strategies. Parenteral administration via intravenous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular routes circumvents gastrointestinal barriers altogether, providing complete systemic bioavailability and enabling rapid therapeutic action in acute conditions such as acetaminophen toxicity or oxidative crisis. However, this approach is not without drawbacks, as rapid-onset adverse effects—including nausea, emesis, and vasomotor instability—may emerge within minutes of intravenous administration, necessitating careful monitoring and dose adjustments in sensitive or critically ill veterinary patients (Parli et al., 2023).

While NAC’s pharmacological versatility is widely recognised, its clinical application in dogs and cats is fundamentally limited by bioavailability challenges, metabolic variability, and a lack of species-specific pharmacokinetic understanding. Addressing these limitations will require a multifaceted research approach that integrates advanced formulation development, rigorous species-specific pharmacokinetic modelling, and carefully designed clinical trials. Progress in these areas will not only optimise NAC delivery and therapeutic efficacy, but also enable its evolution from a broadly applied antioxidant to a precision-tailored veterinary therapeutic. Ultimately, unlocking NAC’s full potential in veterinary medicine hinges on bridging the current mechanistic and translational knowledge gaps to deliver consistently effective and targeted interventions for canine and feline patients.

Pharmacokinetics and Dosing Considerations

Endogenous plasma NAC concentrations in mammals typically range between 23.3 and 137.7 nM (Dodd et al., 2008), reflecting the compound’s role in baseline cysteine and glutathione homeostasis. In cats, pharmacokinetic profiling has revealed relatively short elimination half-lives of approximately 0.78 h following intravenous administration and 1.34 h after oral dosing, with steady-state plasma concentrations (~71 µg/mL) achievable via continuous infusion at a rate of 23 mg/kg/h (Sun et al., 2023). For lower therapeutic plasma targets (<5 µg/mL), chronic oral administration at dosages around 100 mg/kg per day is generally sufficient, under the assumption of linear pharmacokinetics and minimal accumulation over time. In acute toxicological contexts, such as feline acetaminophen poisoning, frequent maintenance dosing every three hours is typically required to counterbalance the drug’s rapid systemic clearance, maintain effective plasma levels, and sustain replenishment of intracellular glutathione pools.

In contrast, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data specific to dogs remain sparse. Preliminary clinical observations and case reports suggest that extended treatment durations (>48 h), or combination regimens incorporating adjunctive antioxidants such as vitamin E, may confer additional therapeutic benefits in hospitalised canine patients (Hagen et al., 2021). However, in the absence of rigorously controlled pharmacokinetic studies, optimal oral absorption profiles, metabolic processing pathways, dosing intervals, and systemic exposure, thresholds remain largely undefined in this species. This knowledge gap severely limits the precision of current veterinary dosing recommendations and highlights the urgent need for targeted canine pharmacological investigations. Specifically, future studies should aim to map the absorption kinetics across gastrointestinal compartments, characterise species-specific hepatic and renal metabolic clearance mechanisms, and establish evidence-based dosing regimens tailored to canine physiology and clinical indications. Without such foundational data, efforts to refine NAC therapeutic applications in dogs will remain largely empirical, impeding progress toward precision veterinary interventions.

Mucolytic Effects of N-acetylcysteine on Respiratory Disorders in Dogs and Cats

N-acetylcysteine is a well-established mucolytic and antioxidant agent with promising therapeutic potential in the management of inflammatory airway diseases marked by excessive mucus production (Baraldi et al., 2025). It is commercially available in various formulations, including injectable, oral, and aerosol preparations. In feline patients, NAC has been employed in the treatment of both acute and chronic bronchopulmonary disorders, which are commonly characterised by dyspnoea and the accumulation of persistent mucus secretions (Mokra et al., 2023).

In conditions such as asthma, the accumulation of highly viscous mucus can obstruct airway lumens, exacerbate bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and contribute to clinical deterioration (Abrami et al., 2024). Inhaled NAC disrupts the disulfide bonds within mucin glycoproteins, thereby modulating ligand-protein interactions and altering protein conformation (Raghu et al., 2021). The mucolytic action of NAC primarily results from its ability to cleave these disulfide linkages in cross-linked mucus matrices (Tieu et al., 2023).

Beyond its mucolytic effects, NAC has demonstrated the capacity to scavenge oxygen free radicals, thereby mitigating lung reperfusion injury following deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (Qu et al., 2013). In human clinical settings, NAC administration after off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery has been associated with a reduction in vascular resistance index and a decreased incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications (Kim et al., 2011; Feng et al., 2019; Mavraganis et al., 2022).

In canine models undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), NAC supplementation has been linked to increased malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, indicative of oxidative stress and activation of endogenous antioxidant pathways (Qu et al., 2013; Gregory and Binagia, 2022). CPB in dogs frequently elicits a systemic inflammatory response, contributing to multi-organ dysfunction, including pulmonary injury (Fujii et al., 2020). Consistent with prior findings, NAC treatment significantly attenuated lipid peroxidation in lung tissues following CPB, suggesting a protective role against CPB-induced acute lung injury (Qu et al., 2013).

Conversely, Reinero et al. (2011) reported that aerosolised NAC administration, compared to saline, significantly increased airway resistance and produced a moderately significant elevation in plateau pressure (Pplat) in cats. Pplat serves as a key indicator of respiratory tract resistive pressure, reflecting variations in airway resistance due to intraluminal secretions, bronchoconstriction, or inflammation. The irritative effects of NAC on the airway mucosa may be attributed to its acidic properties, given its pKa of 2.2 (Robin et al., 2017; Rogliani et al., 2024).

In addition to its pulmonary applications, NAC has been shown to exert mucolytic activity in bile, where it facilitates the degradation of macromolecular proteins, including mucin, into smaller peptides and subsequently into amino acids, thereby reducing bile viscosity (Boullhesen-Williams et al., 2019). Moreover, NAC enhances hepatic antioxidant capacity by supporting glutathione synthesis and reducing oxidative stress (Zybleva et al., 2023). Clinically, NAC has been used to aid in the dissolution of gallbladder mucoceles and biliary sludge, potentially reducing the need for surgical intervention. It is also applied intraoperatively during cholecystectomy to irrigate the biliary tract and ensure the patency of the common bile duct (Boullhesen-Williams et al., 2019; Osailan et al., 2023). In one case report, the administration of 2 mL 20% NAC via a cholangiogram catheter in a canine patient led to rapid bile breakdown and the resolution of associated clinical signs (Boullhesen-Williams et al., 2019).

Effects of N-acetylcysteine on pathogens in dogs and cats

N-acetylcysteine is a recognised non-antibiotic compound with demonstrated antibacterial activity (Oliva et al., 2023). Sarian et al. (2022) reported that NAC effectively inhibits the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species. Furthermore, studies by May et al. (2019) and Jeon et al. (2024) demonstrated that NAC suppresses the replication of otitis-associated pathogens in canine models, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic agent in veterinary medicine. The proposed mechanisms underlying NAC antibacterial effects include competitive inhibition of cysteine uptake by microbial cells and disruption of protein structures containing sulfhydryl groups (Pedre et al., 2021; Eligini et al., 2022).

Lima et al. (2023) found that NAC exerts a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa, reducing both bacterial growth rate and inoculum size. As a result, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) decreased to a range of 2–20 µg/mL. In a separate study, NAC was used as an adjuvant treatment against fluoroquinolone- and ciprofloxacin-resistant P. aeruginosa strains associated with chronic otitis media, showing efficacy at concentrations ≥0.5% (5,000 µg/mL) (Lea et al., 2014; Youngmin and Bae, 2021). These findings suggest that NAC may serve as a valuable adjunct to conventional antibacterial therapies.

In an in vitro investigation, Son and Bae (2021) evaluated the effects of NAC in combination with gentamicin, enrofloxacin, and polymyxin B against P. aeruginosa isolates from dogs with external otitis. NAC demonstrated inhibitory effects on both biofilm formation and planktonic bacterial populations, proving effective against all 14 tested isolates. However, findings from May et al. (2019) indicated that NAC did not consistently enhance the antibacterial efficacy of enrofloxacin or gentamicin. In some cases, its inclusion had no effect or even reduced the antibacterial activity of these agents against certain bacterial strains.

While NAC’s antibacterial properties have received considerable attention, its therapeutic benefits may also extend to viral infections mediated by oxidative stress. For instance, canine parvovirus (CPV) infection has been linked to oxidative damage resulting from mitochondrial membrane disruption, pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and NS1 protein-induced DNA injury (Nykky et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2024). Conventional supportive treatment—typically comprising intravenous fluids, antiemetics, antibiotics such as ceftriaxone-tazobactam, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like meloxicam—does not significantly reduce nitric oxide (NOx) and MDA levels or improve glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity. In contrast, adjunctive NAC administration markedly reduced NOx and MDA concentrations while enhancing GST activity in CPV-infected dogs (Gaykwad et al., 2018; Faghfouri et al., 2020).

In addition to these effects, NAC has been shown to inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase, reduce serum lipid peroxidation, and restore non-enzymatic antioxidant defences (Kasperczyk et al., 2014; Shahripour et al., 2014; Tieu et al., 2023). One proposed mechanism involves the suppression of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1), two key transcription factors regulating the inflammatory response to oxidative stress (Santus et al., 2024). In feline medicine, NAC’s antioxidant properties may also contribute to reduced susceptibility to feline coronavirus infection, a disease in which oxidative stress and disruption of redox balance are known pathogenic factors (Izquierdo-Alonso et al., 2022).

Detoxifying Effects of N-acetylcysteine on Dogs and Cats

Acetaminophen overdose results in the accumulation of toxic metabolites, such as p-aminophenol, in the red blood cells of both dogs and cats. These species lack the enzyme N-acetyltransferase 2, which is critical for the detoxification of these metabolites (McConkey et al., 2009; Coen, 2015). Clinically, NAC is widely employed as an antidote to mitigate acetaminophen-induced toxicity in cats (Avizeh et al., 2010). When administered orally, NAC is efficiently absorbed through the gastrointestinal mucosa and transported to the liver via the portal circulation, where it facilitates detoxification processes. As a result, the oral route is generally preferred for therapeutic use (Licata et al., 2022). However, oral administration is contraindicated in patients with coma, persistent vomiting, or those previously treated with activated charcoal, as these conditions may reduce therapeutic efficacy and increase the risk of aspiration (Fixl et al., 2017; Heard, 2018).

The protective effect of NAC is primarily attributed to its high content of sulfhydryl groups, which serve to replenish serum sulfate and glutathione levels, thereby reducing acetaminophen toxicity (Özkan, 2017; Yang et al., 2022). Avizeh et al. (2010) demonstrated that a single oral dose of NAC at 100 mg/kg is effective in treating acetaminophen poisoning in cats. Mechanistically, NAC enhances the synthesis of cysteine and mercapturic acid conjugates, enabling glutathione to neutralise the hepatotoxic metabolite of acetaminophen more rapidly and efficiently, thereby minimising hepatocellular injury (Dodd et al., 2008; Licata et al., 2022).

Beyond acetaminophen toxicity, NAC is also recommended for managing hepatic failure arising from other drug-induced complications, such as xylitol poisoning in dogs (Li et al., 2022). It exerts hepatoprotective effects by increasing intracellular glutathione concentrations and stabilising mitochondrial membrane potential, thereby protecting endothelial cells from genotoxicity and necrosis (Mokhtari et al., 2017). Additionally, NAC has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy as an adjunct treatment in cases of heavy metal toxicosis and poisoning by Amanita species mushrooms (Buur et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2022).

Antioxidant Effects of N-acetylcysteine on Dogs and Cats

The antioxidant activity of NAC is mediated through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Directly, NAC acts as a scavenger of specific oxidant species, including hypochlorous acid and nitrogen dioxide, neutralising these reactive compounds and thereby mitigating oxidative damage (Aldini et al., 2018; Pedre et al., 2021; Kalyanaraman et al., 2022; Shakya et al., 2023). Indirectly, NAC functions as a prodrug for cysteine. Following the removal of its acetyl group, NAC is metabolised into N,N-diacetylcystine and N-acetylcystine dimers, which covalently bind to plasma proteins and are subsequently deacetylated to release free cysteine (Sommer et al., 2020). Cysteine is a critical substrate for the synthesis of GSH, a central component of the cellular antioxidant system and a cofactor for various enzymatic antioxidant reactions (Averill-Bates, 2023).

During oxidative stress, intracellular GSH reserves become depleted, compromising antioxidant defences. NAC supplementation helps restore these levels by replenishing cysteine availability (Raghu et al., 2021). However, despite the importance of this pathway, the kinetics of endogenous GSH repletion following NAC administration remain poorly characterised, particularly in high-turnover organs such as the liver, kidneys, and pancreas (Dodd et al., 2008; Yurttaş et al., 2022). Additionally, NAC contributes to redox homeostasis by reducing disulfide bonds and restoring intracellular thiol pools, thereby modulating reactive oxygen species such as the superoxide anion (O₂⁻) (Altomare et al., 2020; Altomare et al., 2022; Eligini et al., 2022; Mlejnek, 2022). Its relatively small molecular weight (163.29 g/moL) supports efficient cellular uptake and redox regulation.

In veterinary applications, NAC has demonstrated efficacy in managing oxidative stress in canine hepatopathies. In dogs with cholangiohepatitis and hepatitis, antioxidant therapy with NAC during the initial 48 hours of hospitalisation significantly increased plasma cysteine concentrations and prevented further depletion of red blood cell GSH levels (Tieu et al., 2023). Furthermore, NAC has been shown to reduce methaemoglobin formation in dogs (Viviano and VanderWielen, 2013). In chronic conditions such as degenerative joint disease and chronic active hepatitis, NAC functions both as a cysteine precursor and as a direct free radical scavenger, contributing to long-term oxidative stress management (Raghu et al., 2021; Yahia et al., 2024).

NAC’s antioxidant properties have also been explored in reproductive medicine. Its inclusion in semen extenders has been associated with improved sperm motility in dogs (Zhitkovich, 2019; Hakimi et al., 2024). Studies by Michael et al. (2010) and Al-Dean and Hammoud (2024) reported that low concentrations of NAC improved motility parameters, while higher concentrations (2.5 and 5 mM) induced hyperactivated motility, potentially leading to premature acrosomal reaction and compromised fertility (Alahmar, 2019). Moreover, NAC’s intrinsic acidity (pH 1.5–2.0) may further impair sperm quality when used at excessive concentrations (Michael et al., 2010; Al-Dean and Hammoud, 2024).

Despite its therapeutic advantages, NAC exhibits lower antioxidant potency compared to other thiol-containing molecules. According to Aldini et al. (2018), the hierarchy of antioxidant activity among thiols is cysteine > glutathione > NAC, indicating that NAC is the least potent under equimolar conditions. Nevertheless, it offers greater aqueous stability, making it a more practical and reliable agent for clinical use (Pedre et al., 2021). Interestingly, thiol compounds, including NAC, may exhibit pro-oxidant behaviour under certain conditions, contributing to the formation of hydroxyl (•OH) and thiyl (RS•) radicals (Aldini et al., 2018).

Limitations and Future Perspectives

While the present review synthesises the current body of knowledge on the use of NAC in canine and feline medicine, several important limitations within the existing literature must be acknowledged. Many published studies are constrained by small sample sizes, non-standardised dosing protocols, or an overreliance on extrapolated data from human or rodent models. Moreover, the evidence base is often fragmented and, at times, contradictory, particularly regarding NAC’s capacity to modulate oxidative stress, inflammatory cascades, and immune responses in chronic disease contexts. This inconsistency underscores the urgent need for rigorous, species-specific investigations to clarify NAC’s pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and therapeutic profiles in veterinary settings.

Future research priorities should include the design and execution of adequately powered, controlled clinical trials that systematically account for interspecies pharmacokinetic variation, disease stage, comorbid conditions, and potential breed-specific metabolic differences. Expanding the scope of inquiry beyond traditional applications, such as hepatoprotection and toxicosis management, into emerging areas like neuroprotection, oncological support, and immunomodulation, may uncover novel and clinically transformative uses. Meanwhile, advances in formulation science, including the development of targeted delivery systems, lipophilic derivatives, and next-generation carriers, hold promise for overcoming current bioavailability limitations and improving systemic exposure, pharmacological precision, and clinical efficacy.

Progress in these areas will require not only rigorous experimental design but also close interdisciplinary collaboration between pharmacologists, formulation scientists, veterinary clinicians, and regulatory stakeholders to ensure translational relevance, safety, and real-world applicability. Comparative and translational research models may also accelerate knowledge generation, bridging gaps between veterinary and human pharmacology. Finally, it is essential to recognise that even as the scientific evidence base strengthens, practical challenges, including regulatory approval, cost considerations, and formulation accessibility, will shape how effectively NAC is integrated into routine veterinary care.

By addressing these scientific, translational, and implementation challenges, future research can position NAC not merely as a general-purpose antioxidant or detoxifying agent, but as a precision-tailored therapeutic tool—one optimised for the unique physiological and clinical needs of canine and feline patients, and capable of advancing the quality, effectiveness, and evidence-based sophistication of modern veterinary medicine.

Conclusion

N-acetylcysteine is a multifaceted therapeutic agent with broad applications in veterinary medicine for both dogs and cats. Its clinical utility encompasses its role as an effective antidote for acetaminophen toxicity, a mucolytic agent in the management of respiratory disorders, and a cysteine precursor that enhances glutathione synthesis, thereby mitigating oxidative stress. In addition to its antioxidant and detoxifying functions, NAC exhibits antimicrobial activity and plays a beneficial role in modulating bile viscosity and hepatic metabolism. Despite these advantages, NAC’s use may be limited by adverse effects such as gastrointestinal discomfort, including nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, under certain conditions, NAC may paradoxically exert pro-oxidant effects. While its therapeutic potential is substantial, further investigation is warranted to elucidate its pharmacokinetic profile, optimise dosing regimens, and evaluate its long-term safety and efficacy in veterinary species.