Use of BeeSmoke smoker pellets during the active beekeeping season

I.Dukarić, D. Pavliček*, M. Đokić and I. Tlak Gajger

Ivana DUKARIĆ MALČIĆ1, dukaric.ivana1@gmail.com, orcid.org/0009-0005-7022-6253; Damir PAVLIČEK2* (corresponding author),

pavlicek.vzk@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-1772-6257; Maja ĐOKIĆ3, dokic@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-3071-6208;

Ivana TLAK GAJGER4, itlak@vef.unizg.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-4480-3599

1 Veterinary Center Studenci, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia

2 Veterinary Department Križevci, Croatian Veterinary Institute, 48260 Križevci, Croatia

3 Laboratory for Residue Control, Department of Veterinary Public Health, Croatian Veterinary Institute, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

4 Department for Biology and Pathology of Fish and Bees, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

![]() https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.5

https://doi.org/10.46419/cvj.57.2.5

Abstract

An innovative and sustainable approach to beekeeping involves using commercially available pellet fuels, such as BeeSmoke Forte or BeeSmoke, for daily work in the apiary. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of these pellets, including their impacts on the strength and behaviour of honeybee colonies, their ability to reduce the number of parasitic mites Varroa destructor, and the presence of insecticide/acaricide residues in honey. During the study, the smoke produced by burning BeeSmoke Forte, BeeSmoke, and pure wood pellets in a smoker caused no changes to honeybee behaviour and resulted in no fatalities. BeeSmoke Forte and BeeSmoke pellets increased the number of fallen parasitic mites V. destructor. Furthermore, honey collected before and after the use of pellets and analysed for the presence of insecticide/acaricide residues gave negative results, indicating that the honey extracted during the active beekeeping season when these fuels were used is safe for bees and for human consumption.

Key words: honeybee colonies; smoker pellet fuels; good beekeeping practices; Varroa destructor

Introduction

Honeybees are social insects living in a well-organised colony in which they perform complex tasks, such as house bees in the hive, or forager bees that collect food and water in nature. Communication, wax comb construction, defence, and the division of labour are just some behavioural patterns that honeybees have developed to live successfully in social communities. Worker honeybees collaborate in building honeycombs, collecting food, cleaning honeycomb cells, and nourishing the brood (Vidal Naquet, 2015; Siefert et al., 2021). Each member of the honeybee colony has an age-specific role, and survival and reproduction require the combined efforts of the entire colony. The social structure is maintained by the presence of a queen, drones, and numerous worker bees, and depends on an effective chemical communication system. The reproduction and development of the colony depends on the queen’s productivity, stored food quantities, and colony strength (Tautz, 2008; Connor, 2008). As colony size increases to several tens of thousands of worker bees, so too does the colony’s production efficiency.

Colony behaviour is a complex system with well-defined components of environmental influences, maturation and hereditary traits (Lin et al., 2024). A key advantage of eusociality is the joint defence of the brood and food stores, with nest defence playing the most significant role in honeybee biology (Breed et al., 2004), while the innate defensive behaviour or aggressiveness of guard bees is crucial in ensuring the colony’s defensive response (Hunt, 2007). There is a known correlation between defensive behaviour and colony strength (Kovačić, 2018). Honeybees generally attack only in defence of the colony, but will also attack if they are seriously disturbed by external factors. Common factors that can stimulate the honeybee colony to take an active defence include alarm pheromones, vibrations, altered carbon dioxide concentrations, and dark colours (Urlacher et al., 2010). The stinging apparatus is the main defensive mechanism used against other insects, foreign bees, humans, and animals. The stinger in bees (worker bees, queen bees) is located in the posterior part of the abdomen and is constructed from preformed scales of the 11th and 12th segments of the exoskeleton (Davis, 2011). The poisonous gland that produces the venom is connected to the stinger. The defensive behaviour of adult female bees results in stinging, i.e., the application of bee venom to the victim’s sting wound. Honeybee venom can cause a localised reaction around the sting wound, such as inflammation with symptoms of pain, heat, and itching, up to systemic allergic reactions that can end in anaphylactic shock or, in extreme cases, death (Golden et al., 2007; Paoli et al., 2021).

Beekeepers have developed ways to protect themselves from honeybee stings while handling a honeybee colony. One way is to use a manual smoker as a basic tool to apply smoke into the hive. The smoke causes no harm to the adult bees, interfering only with their sense of smell so they do not react to alarm pheromones that can trigger an alarm response in other adult worker bees and prepare them for attack (Alaux and Robinson, 2007). Pheromones are substances that an individual bee secretes and are then perceived by other individuals of the same species, as a form of transmission of chemical information (Le Conte et al., 2001). Pheromones play a pivotal role in maintaining the social structure and efficiency of the colony, enabling communication between members and the coordination of activities such as defence, reproduction, and foraging. Receiving pheromone information releases a specific reaction in other individuals, which can be behavioural, developmental, or physiological (Kane and Faux, 2021).

The use of smoke in beekeeping is a well-established practice in hive management that affects honeybee behaviour. Scientific studies have explored the effects of smoke on honeybees, offering insights into the mechanisms behind this technique. The smoke prompts the adult bees to prepare to leave the hive. In doing so, they take some of the honey, thinking that they will require extra energy to find a new home. After feeding on honey, the honey sac of bees becomes so full that it makes it difficult for them to sting, resulting in calmer behaviour. They are also slower and somewhat dazed, likely due to the effects of smoke exposure on their ability to extend the stinger (Gage et al., 2018). Research has indicated that smoke temporarily disrupts the olfactory senses, impairing their ability to detect alarm pheromones. This interruption in chemical communication leads to a reduction in defensive behaviours (Gage et al., 2018). These studies have provided a scientific basis for the traditional use of smoke in beekeeping, highlighting its role in modulating honeybee behaviour to facilitate hive management.

Beekeepers use a variety of materials as fuel for smokers for effective hive management. Common fuels include pine needles, wood shavings, paper egg cartons, newspapers, pellets, rotten wood, and dried mushrooms. These materials produce cool, white smoke that helps to calm adult bees during hive inspections. Additionally, commercial products, designed for convenience and efficiency, are available that beekeepers can use as smoker fuel. Compressed wood pellets, for example, are popular because they burn cleanly and produce prolonged smoke. One such product analysed in this study is the innovative pelleted fuel line, BeeSmoke. After the smoke dissipates, honeybees regain their sensitivity to pheromones within 10 to 20 minutes. Therefore, beekeepers must be cautious about the materials they choose to use as smoker fuel. Caution is needed concerning the temperature of the smoker while managing bees, as excessive heat can harm their wings, and so the smoker should be kept at least 5 centimetres away from the adult bees. The choice of smoker fuel can also greatly affect the quality of the smoke and the ease of hive management. Beekeepers typically select fuels based on factors such as availability, burn duration, and the type of smoke produced, ensuring effective management of the honeybee colony.

Parasitic mites pose the greatest challenge to beekeeping today. Honeybee colonies are affected by three primary species of obligate parasitic mites: Varroa spp., Acarapis woodi, and Tropilaelaps spp. (Traynor et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2024). Among these, the V. destructor mite is currently regarded as the most dangerous parasite affecting Western honeybees (Posada-Florez et al., 2019), as European honeybee races lack effective defence mechanisms against these parasites. Varroosis is listed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and national regulations impose mandatory control treatments for honeybee colonies to combat this condition. In addition to the use of medicinal products, biological breeding techniques play a crucial role in hive biosecurity management. These biological measures include human intervention in the shape of sacrificing worker and/or drone brood, placing new frames in the hive, applying powdered sugar, insulating the queen, and artificially interrupting bee brood during the active beekeeping season (Lin et al., 2023).

This paper presents an innovative approach to sustainable beekeeping by evaluating the effectiveness of two commercially available smoker pellet fuels: BeeSmoke Forte and BeeSmoke. The study examines the behaviour of honeybee colonies and the potential acaricidal effect of each fuel on V. destructor mites at various intervals following the use of the smoker. Additionally, the strength of the honeybee colonies was assessed before and after the application of BeeSmoke pellets, and honey samples from the hives were analysed for pesticide residues, including acaricides.

Material and Methods

Location of the experimental apiary

The experiment was conducted at an apiary located in rural northern Croatia, which operates as a stationary facility. Honeybee colonies within the apiary are housed in Langstroth-Root type hives, which are vertical hives of standardised components and dimensions. The main natural food sources in the region are acacia and chestnut. The apiary consists of 30 honeybee colonies. For the experiment, 15 colonies were selected and divided into three groups, each of five colonies: two experimental groups and one control group. Each group was positioned several metres apart.

Estimation of the strength of honeybee colonies

To assess the strength of honeybee colonies, a specific formula is used that incorporates various parameters, including the number of frames populated with adult bees and the percentage of frame area filled with honeybee brood. According to standard methods for estimating the strength parameters of A. mellifera colonies, the area of common frame types and the expected density of bees when a frame is fully covered with adult bees are taken into account. For the Langstroth Root type frame, one side of the frame can accommodate approximately 1400 workers and drone bees. To calculate colony strength, the estimated honeycomb area occupied by the brood is multiplied by four and then added to the estimated number of adult bees (Delaplane et al., 2013).

Applying smoke to the beehives

Three smokers of equal volume were used for the experiment. Smoke was blown into the hives early in the morning when the worker bees had not yet left the hive to forage. Kindling was placed in each smoker, and a fire was ignited. The first smoker (A) used BeeSmoke Forte pellets, the second smoker (B) used BeeSmoke pellets, and the third group smoker (C) used pure wood pellets and served as the control group. An equal amount of pellet fuel was placed in each smoker. After ignition, smoke was blown into each hive five times under the cover of the hive during the summer. The smoking procedure was repeated five times for a month, at equal intervals. After treating the honeybee colonies with smoke using the specific type of fuel, treatment effectiveness was monitored. A sample of adult worker bees (collected in a 120 mL plastic cup with a lid) was taken from each hive, both before treatment and after the examination in the apiary. A sample of 250 to 300 worker bees was taken from each hive both before and after the smoker treatment for laboratory diagnostics. This process aimed to determine the presence and morphological identification of the V. destructor parasite (Boecking and Genersch, 2008; Ellis et al., 2010; Rosenkranz et al., 2010; Dietemann et al., 2012). These samples were sent for laboratory analysis to determine the presence of and identify the morphology of the V. destructor parasite. Honeybee samples were stored in the freezer until analysis.

The decline in V. destructor mites within the hives was monitored at three specific intervals after treatment. After applying smoke from a specific fuel, the number of fallen V. destructor mites was counted on the plates of the anti-varroa floor of individual hives. The count of fallen mites took place 3, 6, and 24 hours after each smoking treatment. After each count, the plate on the hive floor was cleaned. A magnifying glass was used to assist with the counting process.

The treatment of all honeybee colonies took place in the early morning hours, on average around 7 a.m., and at an average temperature of about 17 °C. The treatment took place on five days, four of which were during rainy weather, ensuring that nearly all the adult bees were present in the hive at the time of treatment.

Honey analyses

Honey analysis was conducted on two composite samples taken from honeycombs, one before and one after the experimental study. Determination of 151 multiclass pesticide residues (organochlorines, organophosphates, pyrethroids, carbamates, neonicotinoids, etc.) was performed using the QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) approach in combination with liquid and gas chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS). After adding water and acetonitrile as an extracting solvent, citrate salts (trisodium citrate dihydrate and disodium citrate sesquihydrate) were used in the first extraction step, followed by the primary secondary amine (PSA) with magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) as the cleanup sorbent in case of LC-MS/MS analysis and EMR-Lipid sorbent and EMR-Polish Tube before GC-MS/MS analysis, respectively. The analytical method was validated in accordance with the SANTE/12682/2019 guidelines, obtaining acceptable recovery (70–120%) and precision, expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD <20%) (SANTE, 2019). For sample quantification, matrix-matched calibration curve is performed by spiking blank honey extract at a minimum of three concentration levels, including the limit of quantification (LOQ), ranging from 0.001 to 0.01 mg/kg.

Behavioural traits

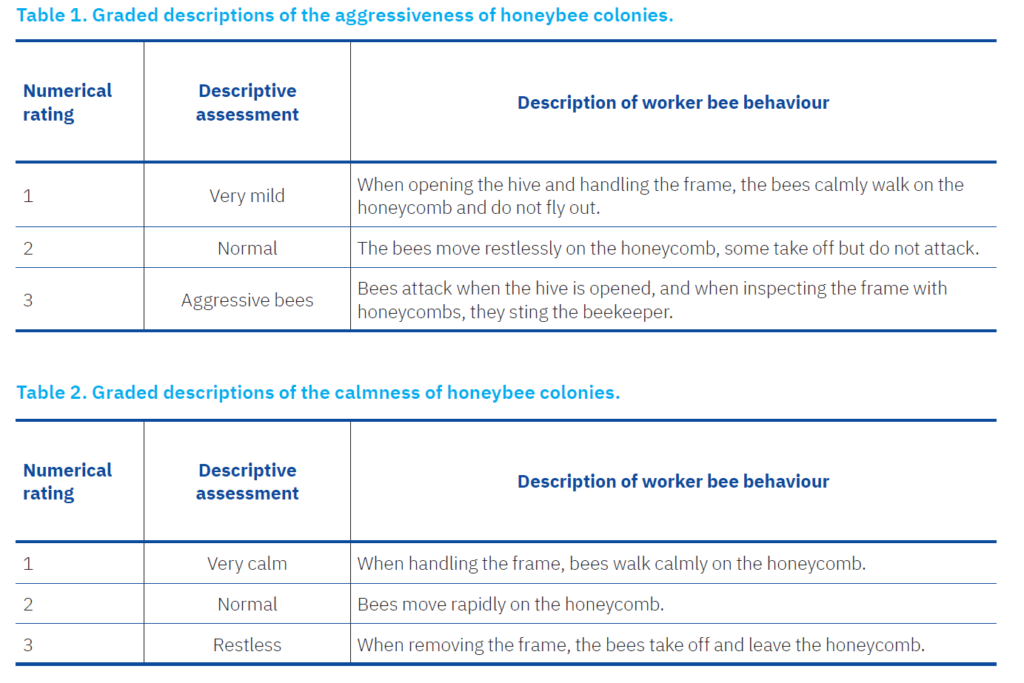

Throughout the work with each honeybee colony, we monitored adult bee aggressiveness and calmness. We assessed these characteristics by assigning a numerical score, with each score reflecting specific behaviours of the worker bees, as detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Statistical processing and presentation of data

The assessment results regarding the strength of honeybee colonies and the evaluation of the smoke efficiency of various fuels used in a smoker to test the impact on reducing V. destructor mite populations were processed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 8 software. After processing, the data were graphically presented in GraphPad Prism 8 for clearer comprehension. The behavioural traits of the honeybee colonies are presented in tables, while the analytical results of the honey samples are described descriptively.

Results

Figure 1 shows the estimated strength of honeybee colonies in the experimental and control groups. Honeybee colonies in the experimental group treated with smoke from the commercially available BeeSmoke Forte pellets were the strongest (** P<0.05). In contrast, the weakest colonies were found in the control group, and the difference between these two groups was significant (** P<0.05). Although the honeybee colonies treated with BeeSmoke pellet smoke were stronger compared to the control group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Behavioural characteristics of honeybee colonies

During the smoking of honeybee colonies with BeeSmoke and BeeSmoke Forte pellets, the behaviour of the honeybee colonies was assessed based on the descriptions in Tables 1 and 2. The aggressiveness of all honeybee colonies was rated with a score value of 2, indicating that the adult bees moved calmly on the honeycomb, with some taking flight, but without attacking. The control group of honeybee colonies displayed similar results. The overall calmness of the honeybee colonies in all observed groups was also rated with a value of 2, indicating that adult bees moved swiftly on the honeycomb.

Effectiveness of smoke on V. destructor mite fall

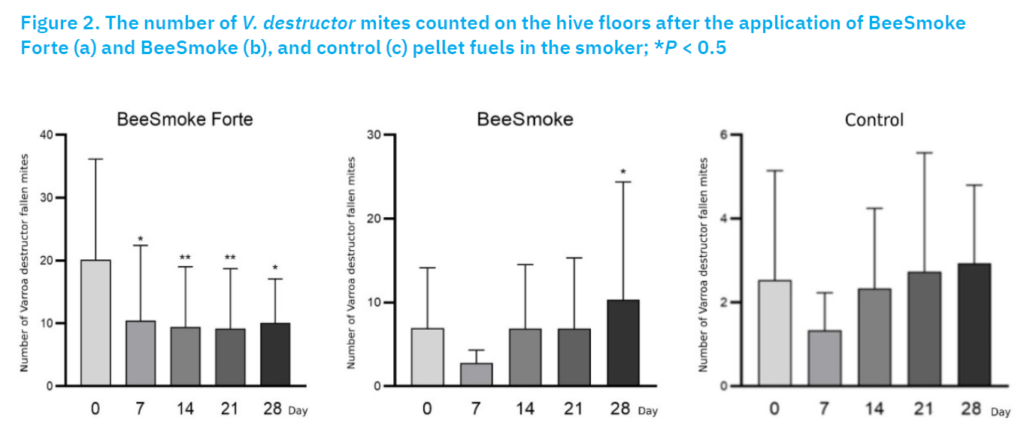

Figure 2 illustrates the number of V. destructor mites counted on the hive floors after using BeeSmoke Forte pellets during hive management. The figure clearly shows that the highest count of V. destructor mites was observed after the first application of smoke in the honeybee colonies. Following the initial treatment, the number of counted mites decreased significantly.

Pesticide residues in honey

Honey samples were analysed for the presence of 151 pesticides. In the sample collected before the experimental application of the smoker, the concentration of coumaphos was measured at 0.01 mg/kg. After the final application, this concentration increased to 0.013 mg/kg. The maximum residue levels (MRLs) for coumaphos in honey and other apian products is set at 0.1 mg/kg (EC, 2017).

Discussion

A smoker is an essential tool in beekeeping, often used to calm adult honeybees, as it reduces the likelihood of stings and makes the beekeeper’s work more manageable. In beekeeping practices, various materials serve as smoker fuel. The market offers a variety of commercial fuels, which come with several recommended advantages over traditional materials. During the active beekeeping season, we monitored the effects of two innovative fuels on the strength and behaviour of honeybee colonies, the decline of the parasitic mite hive population, and the safety of honey by determining concentrations of pesticide residues. In this study, a total of 15 honeybee colonies were observed. The honeybee colony has evolved a coordinated defence system against foreign bees and other intruders for the sake of survival (Kuszewska and Woyciechowski, 2014; Nouvian et al., 2016). Smoke is known to disrupt the typical defensive behaviours of bees (Lomele et al., 2010; Gage et al., 2018) by temporarily interfering with their olfactory senses, preventing them from detecting alarm pheromones. Gage et al. (2018) examined how different types of smoke fuels affect individual bees under controlled laboratory conditions. The findings revealed that while smoke does not influence the likelihood of a bee pulling out its stinger, it does decrease the chance of venom being released from the stinging apparatus. A single drop of venom on a bee’s stinger is believed to correspond to its level of distress; therefore, smoke appears to lower the likelihood of venom secretion. The Gage et al. (2018) observed that the behaviour of honeybee colonies exposed to smoke was similar to that of control colonies, indicating no significant differences. Regardless of the fuel type used in the smoker, the smoke led to a reduced release of alarm pheromones. In each honeybee colony, the strength of the honeybee colonies was evaluated. It was determined that the strongest group was the one treated with BeeSmoke Forte pellets, followed by the group treated with BeeSmoke pellets, while the control group was the weakest.

Plants have developed a variety of defence mechanisms against parasites and pests, which often include secondary metabolites. These compounds may act as repellents, discourage feeding, serve as antimetabolites, or even contain insecticidal components within the plant tissues (Lill and Marquis, 2001; Tlak Gajger and Dar, 2021). Consequently, the presence of secondary metabolites in plants used for smoke can have both positive and negative effects on bee colonies. For instance, Eischen and Vergara (2004) studied the impact of volatile substances in the smoke from different plants on bee survival and the parasite Acarapis woodi. Their experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions in incubators, and each treatment lasted for 20 minutes. Notably, none of the fuels used in the smoker caused bee mortality, and the bees recovered within minutes.

Following the findings of Elzen et al. (2001), which indicated that the smoke from certain natural products negatively impacts the parasitic mite V. destructor, this study aimed to investigate the acaricidal effects of BeeSmoke Forte and BeeSmoke fuels in comparison to smoke from wood pellets. By observing and counting the fallen V. destructor mites on the anti-varroa plates placed on the hive floors after using the smoker, we found that the highest number of fallen mites was in the group treated with BeeSmoke Forte, followed by the group treated with BeeSmoke, while the control group of honeybee colonies showed the fewest fallen mites. The average number of fallen V. destructor mites in the group treated with BeeSmoke Forte pellets was 232.4 mites, compared with 113.2 mites in the group treated with BeeSmoke pellets, and just 38.6 mites in the control group. The literature mentions alternative smoker fuels, such as jute material (Gage et al., 2018) and female hop flowers (Van Cleemput et al., 2009). However, beekeepers have expressed concerns about using smoke from tobacco leaves or other complex fuels that contain nicotine, as the intoxicating effects can lead to vomiting or even suffocation of the adult bees, which poses a significant risk during the summer months (Cook and Griffiths, 1985; Gage et al., 2018).

In the first experimental group treated with BeeSmoke Forte pellets fuel, the average number of mites detected was 11.8 before treatment and increased to 12.8 after treatment. In the second group treated with BeeSmoke pellets, the average number of V. destructor parasites before treatment was 7.0, increasing to 18.8 after treatment. In the control group, the average number of identified V. destructor parasites was 5.8 before treatment and 14.2 after treatment. From these data, it is evident that the level of infestation of colonies with the V. destructor mite in all three groups of honeybee colonies was variable. However, from the results of counting the fallen mites after the application of smoke of a particular type of fuel, it is evident that the greatest impact on the fall of mites was from the smoke of BeeSmoke Forte pellets, followed by the smoke of BeeSmoke pellets, and was the lowest after smoke of pure wood pellets. Although no negative effects on adult bees or their behaviour were observed in this study, and since smoker fuels may contain unidentified or unknown ingredients with varroocidal activity, additional research on possible mechanisms of action against the V. destructor mite should be carried out. A total of 151 pesticides were analysed in comb honey, before and after treatment with a smoker, using GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS methods. The results showed no presence of these pesticides above the LOQ. However, low concentrations of coumaphos were detected before and after treatment. These levels can be attributed to biosecurity control measures implemented to manage V. destructor invasion levels, in current and previous years using CheckMite+. This statement can be supported by findings of Kast et al. (2020), who concluded that beeswax exposed to CheckMite+ should not be recycled and reused in new foundations, in order to prevent elevated concentrations of coumaphos and possible detrimental effect on honeybee larvae. The transfer of coumaphos residues inside the hive was evaluated by Luna et al. (2023), who concluded that the high concentrations of this organophosphorus acaricide in bee bread (range LOQ–1.36 mg/kg) ingested by the bee brood resulted in residue detection in all larval stages, ranging from 0.052–0.383 mg/kg (larvae), 0.042–0.059 mg/kg (prepupae), 0.018–0.026 mg/kg (pupae), to 0.022–0.036 mg/kg (newly emerged bees). Nevertheless, a high transfer of residues toward honey was not observed, resulting in the highest detected concentration of 0.049 mg/kg.

Importantly, the concentration of coumaphos in honey found in this study does not exceed the permitted limits set by the European Union (0.1 mg/kg) (EC, 2017). Therefore, honey extracted from the hives treated with the tested pelleted fuels during the active beekeeping season is safe for bees and human consumption.

Conclusions

When applying smoke from burning fuels (BeeSmoke Forte, BeeSmoke, or wood pellets) to the hives, no changes were observed in the usual behaviour or mortality of adult bees in the honeybee colonies. A positive effect of the applied pellet fuels on the behavioural characteristics of the honeybee colony was noted. Both BeeSmoke Forte and BeeSmoke pellets were effective in increasing the removal the parasite mite V. destructor. Additionally, the use of BeeSmoke pellets in the smoker during the active beekeeping season did not impact the quality or safety of the honey produced. Consuming honey collected during this active season, when BeeSmoke Forte and BeeSmoke pellets were used, is not harmful to human health.

References [… show]

Primjena BeeSmoke peletiranog goriva za dimilicu tijekom aktivne pčelarske sezone

Ivana Dukarić Malčić1, dukaric.ivana1@gmail.com, orcid.org/0009-0005-7022-6253; Damir PAVLIČEK2* (dopisni autor), pavlicek.vzk@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0003-1772-6257; Maja ĐOKIĆ3, dokic@veinst.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-3071-6208; Ivana TLAK GAJGER4, itlak@vef.unizg.hr, orcid.org/0000-0002-4480-3599

1 Veterinary Center Studenci, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia

2 Veterinarski zavod Križevci, Hrvatski veterinarski institut, 48260 Križevci, Hrvatska

3 Laboratorij za određivanje rezidua, Odjel za veterinarsko javno zdravstvo, Hrvatski veterinarski institut, 10000 Zagreb, Hrvatska

4. Zavod za biologiju i patologiju riba i pčela, Veterinarski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 10000 Zagreb, Hrvatska

Kao inovativni pristup održivom pčelarstvu u svakodnevni rad na pčelinjaku može se dodati komercijalno dostupna peletirana goriva za dimilicu BeeSmoke Forte i BeeSmoke. Istraživanjem učinkovitosti navedenih goriva bilo je obuhvaćeno određivanje jačine pčelinjih zajednica, ponašajne osobitosti pčelinjih zajednica, učinkovitost primjene na otpadanje nametničke grinje Varroa destructor te analizu na kvantifikaciju rezidua insekticida/akaricida u medu. Prilikom primjene dima zapaljenih goriva (BeeSmoke Forte, BeeSmoke i drvenih peleta) iz dimilice u košnice, na pčelinjim zajednicama nisu uočene promjene uobičajenog ponašanja niti ugibanja pčela. Utvrđeno je učinkovito djelovanje BeeSmoke Forte i BeeSmoke peletiranaog goriva na otpadanje nametničke grinje V. destructor. Analiziran je zreli med prije i nakon primjene dimilice iz pčelinjih zajednica na prisutnost insekticida/akaricida, rezultati kojih su bili negativni, a što potvrđuje da je med sakupljen tijekom aktivne pčelarske sezone u kojoj su primijenjena istraživana peletirana goriva siguran kao hrana za pčele i ljude.

Ključne riječi: zajednice medonosne pčele, peletirana goriva za dimilicu, dobre pčelarske prakse, Varroa destructor